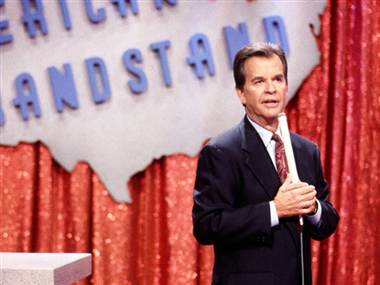

Dick Clark

It's been quite a week for those of us of a certain age; for me in particular. It’s really not the increasing aches and pains and infirmities of age that make getting older such a drag, it's the loss of friends and loved ones —or those whom we may never have met, but touched us in some way–that makes life so occasionally sad.

I had been thinking about Dick Clark quite a bit lately, I'm not sure why. I had known him in three different capacities: I had done some writing and production work for him and his company; he had contributed, as a guest, to several of my own productions; and I had had many great conversations with him, socially, and at professional functions. The latter of the three was always the best.

When I worked for him, the interaction was always perfunctory. Do the job. Do it well. And make it easy for Dick to knock it out and move on to the next project. I never had an issue with him at all. It was always professional and pleasant, but never all that warm and fuzzy. And truthfully, in that capacity, we only crossed paths for mere minutes at a time. In the mid-'80s, he was looking for a new writer-producer for his weekly Top 40 National Music Survey show, and he had his lieutenant, Frank Furino, call and offer me the job (I had previously been a writer for Casey Kasem's American Top 40). I had just assumed a similar position with Dan Ingram's ill-fated Top 40 countdown for CBS and had to pass. I was torn, but Dick was very pragmatic and said, "Frank, call the next person on the list." Dick Clark Productions was not famous for big paychecks, but working with him on a daily would have been pretty cool.

Now when I was producing programming for other companies and networks, I often called on Dick to provide a support interview–an expert voice lending authority on the subject at-hand or providing insight on a performer that he had known for years (Bobby Darin and Paul Anka were his two favorites). Dick never turned down one of my requests. He often made himself available at his Burbank office the very same day of my request, and always within the week. There was no phalanx of handlers and publicists to contend with; when I called, I always got his personal secretary or him directly. In conversation on one occasion, he admitted to me that he had indeed once infamously said that he "was a whore for a buck," yet he never requested any compensation for any of his contributions to my own productions.

I'd arrive and set up my recording gear in his office that sported a grand desk with wooden posts and a trellis-like frame above, and an adjacent wall of bookshelves that seemed to house every tome ever written on the subject of pop music. As a collector myself, I asked him if he had kept a lot of mementos from throughout his career, especially souvenirs from his legendary, multi-artist Caravan of Stars tours. And he said, yes, that he had a warehouse full of records, posters and programs and scripts, but had, in fact, donated quite a few artifacts to the Smithsonian a few years earlier. We'd get down to business —conduct the interview that was required–and he would, unfailingly, give me the pithy, perfect quotes that every writer-producer hopes for when assembling documentary-style programming. He'd smile and ask, "You have everything you need?" And once confirmed, he might not even look up again from whatever was on his desk, from the time I started dissembling my mic and cables until I walked out the door.

Dick ultimately aggregated the radio stations nationwide that were running his programs into a network that, in two different guises, were known as Unistar and United Stations. Ever the superb promoter, Dick would always appear at the semi-annual broadcast conventions in the Unistar suite to glad-hand with affiliates, both potential and established. It was here, and on other social occasions, that I most enjoyed being within his sphere. While most of the visiting deejays, GMs and such would approach him, dumbstruck, for a photo op or an autograph, I had the chance to speak with him at length —sometimes hours–about radio, Rock & Roll, my getting kicked off the "25,000 Pyramid" (another story, another time) and countless other topics.

Once, when we were both attending a conference in Dallas, I had coincidentally found a copy of his 1950s advice guide to teenagers at a local antiquarian bookstore. Of course, I couldn't wait to stick it under his nose at the Unistar suite that night. When I did, he put his arm around my shoulder and announced to the crowd in the room, "I am usually so delighted to have this young man in my presence." (Dramatic pause.) "This is not one of those times." I couldn't have been more pleased to have been his foil.

As I said, I'd been thinking a lot about Dick Clark lately. Talking about him, too. As the consummate broadcaster, no one was better, extemporaneously, in front of a mic or a camera. Nobody. And as successful as he continued to be as an entrepreneur and producer of TV programming, I know that his diminished capacity as a communicator since his stroke weighed heavily on him. Just a few days before his death, I had told someone that I was going to drop him a line, wishing him well and thanking him, not only for our variety of interactions, but for his tremendous influence upon me as a broadcaster and writer.

On Wednesday morning, my friend Bill called to see if I had heard the news. As it turned out, I had been talking to him about Dick just the night before, at precisely the time he had died. There's absolutely no explanation for that. A coincidence, to be sure. But this sort of thing, as friends have pointed out, seems to happen to me quite a bit–a strong sense of premonition or confluence of activity around the passage of those who have influenced me. Unaware that Johnny Carson had been ill, I bundled up a package of magazines commemorating his retirement a decade earlier to send to him at his office in Santa Monica in the hopes of having them signed. And, on a whim that very same day, I went to Costco to pick up the highlights DVD of "The Tonight Show." The breaking bulletin of his death on TV that evening was unfathomable to me. Similar circumstances prevailed when John Lennon died. Again, another story another day.

Dick Clark's impact on pop culture and television programming can't truly be measured. He gently and insidiously helped usher Rock & Roll into the mainstream when conventional media might have left it at the gate...or burned it at the stake. That first wave of post-World War II teenagers —the original American Bandstand generation–was the very first to wield true economic power and enormous influence on fashion, entertainment and manufactured goods. The media cast a spotlight on them, Wall Street sat up and noticed, and Dick Clark was the smooth, polished guy with a foot in both camps that brokered the deal. He may have gone on to other endeavors and greater financial success, but he certainly never surpassed the cultural clout he had in the late-'50s and early-'60s. But for me, right up until the end —and now beyond–he has, and will remain, a profound influence upon me. Thanks, Dick...until next time.